Higher Organizational Continuance Commitment Leads to Higher Employeeas Citizenship Behaviors

Introduction

Despite Industry 4.0, the environment in emerging economies has changed rapidly, but human resources are still the most essential resource for the sustainability of organizations. Understanding how human resources are managed, and what makes them committed to the organization are crucial for an organization to develop and improve in order to obtain better productivity and performance. In other words, human resources affect all aspects of organizational performance (Becker, 2009). In addition, employees play a vital role in organizational activities, such as their social communication with colleagues and managers, and they are perceived as the most valuable assets of organizations in the twenty-first century (Bidarian and Jafari, 2012).

Recently, Vietnam has emerged as one of the best destinations for multinational enterprises to establish their factories because of its cheap and quality workforce. Like other countries, the human resources management field in Vietnam has the same concerns regarding their employees' job satisfaction, employee retention, rate of turnover, and organizational commitment. By analyzing and understanding the reasons behind organizational commitment within an organization, HR departments benefit from a better insight which may result in better HR practices within organizations to make employee retention less problematic. Higher education institutions, particularly universities, have an important role among educational systems in addition to being primarily responsible in developing economies in creating quality workforce for the country. Since 1999, the number of universities and colleges has increased substantially in Vietnam. According to Vietnam's Ministry of Education and Training, by mid-2021, there were 237 universities and institutes (including 172 public, 60 private, and five FDI) of which nearly 28% of higher education institutions were non-public. The total employee strength in the public sector stood at 65,948, and 19,143 in the private sector.

Despite several studies on organizational commitment and organizational citizenship behaviors, very few papers analyze and understand the organizational citizenship behavior of faculty members and staff in higher education, specifically focusing on employees working in post-secondary education levels such as employees in universities, academies, faculties, and institutions providing undergraduate and graduate-level courses in the public or private sector. To bridge this gap, this research is undertaken to examine the influence of each of the components of organizational citizenship behavior on organizational commitment in higher education institutions in Vietnam to assess the weight of each organizational citizenship behavior factor on organizational commitment considering the three types of organizational commitment which are affective commitment, normative commitment, and continuance commitment.

Conceptualization of variables

Organizational commitment (OC)

Organizational commitment is defined as an individual's psychological attachment to an organization. It is crucial for an organization to assess the organizational commitment level of its members as it plays a pivotal role in determining whether an individual is prone to stay committed to the organization for an extended period of time and if this individual will work passionately toward achieving the goals of the organization (Becker, 1960). Many researchers have developed nuanced definitions of organizational commitment as an attentive attitude, and independence with behavioral intentions (Porter et al., 1974). Among these studies, Meyer et al. (1993) offered a model of organizational commitment that included three factors (three-component model—TCM): affective commitment (attachment in organizational activities), continuance commitment (deciding against leaving the organization), and normative commitment (desiring to remain in the organization). Based on TCM, many studies have been conducted to develop the theory of organizational commitment and its consequences, such as Gautam et al. (2005) defined organizational commitment as an attitude of an employee toward the organization which reveals the person's singularity to the organization, i.e., feeling proud of being a part of the organization (Markovits et al., 2010), and the tendency of people to devote themselves and be loyal to the organization (Kim et al., 2005). Devece et al. (2016) claimed that organizational commitment influenced employees' behaviors and attitudes that lead them to stay in the organization. Griffin and Bateman (1986) stated that commitment impacted turnover, absenteeism, and performance of employees.

Affective commitment (AC)

Affective commitment is the term used to define an individual's positive emotional attachment to the organization. According to Meyer et al. (1993), affective commitment is the most "desired" element of organizational commitment. The reason is that an employee who is affectively committed to an organization will identify with the goals of that organization and will desire to be and remain an active part of the organization. This type of employee will stay committed to the organization because they want to do so. Beck and Wilson (2000) also mentioned that employees are committed affectively to staying because they view their career in the organization as congruent to the goals and values of the organization. Mercurio (2015) recalled and stated that affective commitment was found to be an enduring, demonstrably indispensable, and central characteristic of organizational commitment. The study suggested that affective commitment points to individuals in the organization being not only satisfied and happy in the organization but also actively engaged in the organizational activities such as meetings and discussions by giving valuable inputs that will support the growth of the organization.

Continuance commitment (CC)

Based on Meyer and Allen's three-component model, continuance commitment is defined as the type of commitment where an individual thinks that leaving the organization would have a costly impact (Meyer et al., 1993). The employees decide against leaving and stay back in the organization for a longer period of time as they feel they have already contributed and invested a lot of energy to the organization both mentally and emotionally and are attached to the organization. This feeling can be represented by the sense of attachment to their workplace which encourages them to reject any desire to quit because they are strongly invested in the organizational structure.

Normative commitment (NC)

Normative commitment is defined as the level of commitment where an individual feels obligated to stay in the organization because it is the right thing to do (Meyer et al., 1993). The normative commitment represents a moral obligation for employees because their commitment is extended to the need for other individuals in the organization who rely on their decision to contribute to the organization's overall wellness as an active part of it. For instance, normative commitment would be essential to build strong advocates for the organization's cause and promote productivity and reducing absenteeism within the organization. Individuals exhibiting a sense of normative commitment will feel obliged to stay and contribute to the organization constructively.

Organizational citizenship behavior (OCB)

The concept of organizational citizenship behavior as defined by Bateman and Organ (1983) is "Individuals' behavior that is discretionary, not directly or explicitly recognized by the formal reward system, and in the aggregate promotes the efficient and effective functioning of the organization." Organ (1988) proposed the five-factor conceptualization of organizational citizenship behavior. These factors include altruism—related to behaviors that support colleagues even if it is not their responsibility or without any request for help from coworkers; conscientiousness—related to behaviors such as attending organizational events, being punctual, maintaining an orderly workspace, following regulations and reminding everyone to follow them, and voluntarily participating in programs that could help to improve organizational reputation; courtesy—refers to behaviors such as greeting colleagues, checking on others feelings or the status of their projects for helping them if necessary, or advice for colleagues to help them prepare or avoid problems they may face in future; civic virtue—related to employee's concern and interest in important issues of the organization; and sportsmanship—related to "a willingness to tolerate the inconveniences and annoyances of organizational life without complaining." In later works, Podsakoff et al. (2000) and Organ et al. (2006) further refined OCB to include seven major dimensions: altruism (helping behavior); sportsmanship (no complaints about working conditions); organizational loyalty (speaking favorably to the organization); organizational compliance (the acceptance and respect for procedures and rules); individual initiative (make more than what is required or surpass oneself and be creative); civic virtue (general interest in the organization); and self-development (voluntary commitment in training initiatives and be informed about innovations concerning individual's domain). Several empirical studies have tested these dimensions in various contexts of education (Dipaola and Tschannen-Moran, 2001; Esnard and Jouffre, 2008; Deepaen et al., 2015). Robbins and Judge (2012) indicate that organizational citizenship behaviors play an important role in supporting the effective functioning of an organization. Podsakoff et al. (2016) define organizational citizenship behaviors as behaviors that facilitate the performance of tasks within an organization.

Literature review and hypotheses formulation

The relationship between helping behavior and OC

The first main category of organizational citizenship behavior is helping behavior (HE) which is mainly about altruism, which is behavior directed toward other individuals but contributes to the overall efficiency of an organization by enhancing individual performance (Podsakoff et al., 2000; Organ et al., 2006). Individuals who are altruistic will help new colleagues and peers, including third parties, and contribute to the organization by giving their time freely. Primarily found in face-to-face situations, altruism is about helping colleagues who have been absent, volunteering for things that are not required, orienting newcomers, and helping people with heavy workloads. Helping is a fundamental part of perceived organizational support (Eisenberger et al., 1990) and helping one's peers increases perceived organizational support because employees will see that the organization cares about their wellbeing within the organization. It is proven that there is a positive relationship between perceived organizational support and organizational commitment (Meyer and Allen, 1997); this commitment could be facilitated through the helping OCB factor. In this case, the commitment expressed is affective. Thus, the first hypothesis is:

Hypothesis 1: helping behavior has a positive influence on affective commitment.

The relationship between sportsmanship and OC

The second main category of organizational citizenship behavior is sportsmanship, also known as fair play. This behavior exhibits the image of a citizen-like posture of uncomplainingly tolerating the impositions and inevitable inconveniences that may result from work (Podsakoff et al., 2000; Organ et al., 2006). This behavior incorporates the positive and respectful attitude that an individual can project when facing difficulties that happen. The key point is to be supportive no matter what happens. This behavior demonstrates respect, honor, discipline, kindness, inclusion, resilience, perseverance, and so on from an individual. Sportsmanship means that individuals will increase the amount of time spent on organizational endeavors in contrast to complaining and whining, and instead care about the organization. Individuals exhibiting sportsmanship will understand that some unfair situations may occur in the organization and will behave accordingly in a decent manner to avoid conflicts within the organization. According to Moorman (1991) and Moorman et al. (1993), fair treatment by employers reinforces employees' commitment because they would expect to remain fairly treated throughout their tenure in the organization. In return, employees would repay their management by being highly attached to their organization and getting highly involved in its affairs. Hence, it would be appropriate to stay in the organization and be committed to the organization for employees who shows signs of sportsmanship OCB. So, the proposed hypothesis is:

Hypothesis 2: Sportsmanship has a positive influence on normative commitment and continuance commitment.

The relationship between organizational loyalty and OC

The third main category of organizational citizenship behavior is organizational loyalty. This behavior entails protecting and defending the organization against possible external threats and promoting it to outsiders, remaining committed to the organization even in hard times and adverse conditions (Podsakoff et al., 2000; Organ et al., 2006). Employees expressing loyalty would think that staying committed for a long period to an organization is a must, meaning that they will consider loyalty as meaningful, so the adherence to being faithful to the organization will feel costly to them if they leave the organization. Loyal employees will be satisfied and contented with their working environment, superiors, and colleagues. One of the scale items defined by Allen and Meyer (1990) to measure continuance commitment is "It would be very hard for me to leave my organization right now, even if I wanted to." This scale item is reflective of the loyalty factor. The behavior also accompanies a feeling of pride when individuals consider themselves a contributing part of the organization. The loyal individual will fight for the organization and defend the organization's ideology without ceasing. Being loyal to an organization is also a characteristic of normative commitment as Allen and Meyer (1990) outlined: "One of the major reasons I continue to work in this organization is that I believe loyalty is important and therefore feel a sense of moral obligation to remain."

Hypothesis 3: Organizational loyalty has a positive influence on normative commitment and continuance commitment.

The relationship between organizational compliance and OC

The fourth main category of organizational citizenship behavior is organizational compliance (CO), also referred in short as compliance. This behavior refers to individuals acceptance of their internalization and strict adherence to the procedures and policies of an organization (Podsakoff et al., 2000; Organ et al., 2006). In a more practical definition of this behavior, organizational compliance is the fact that employees abide by internal rules of conduct and organizational norms willingly, even if no one is there to assess their dedication to following the regulations defined. In 1977, Folger found out that with high levels of procedural justice reflected in an organization comes a high attachment of the employees to the goals and values of the organization. So, fewer employees intend to quit. Greenberg and Cropanzano (1993) mentioned in their study that procedural justice plays a crucial role in determining employees' attitudes toward their management and can indicate their commitment to their organization. Compliance is associated with procedural justice, suggesting that compliance is a factor associated with normative commitment. Organizational compliance is crucial when building and maintaining a hierarchy in the organization. The feeling of belonging helps individuals to contribute more as they scrupulously adhere to the regulations and laws of the organization. Without organizational compliance, there can be no organizational trust and organizational commitment cannot be ensured.

Hypothesis 4: Organizational compliance has a positive influence on normative commitment.

The relationship between individual initiative and OC

The fifth main category of organizational citizenship behavior is individual initiative. This category is used to describe communications directed to others in the organization with the aim to improve individual and group performance (Podsakoff et al., 2000; Organ et al., 2006). These voluntary actions by individuals go beyond measures to resolve problems and provide constructive solutions to the organizational structure and management. Wasti and Can (2008) have found that when employees have high participation and broader autonomy during decision-making processes, it is likely that their level of commitment will be high. By contributing to the organization constructively, an employee shows signs of normative commitment according to Meyer and Allen's three-component commitment model. Hence, it is logical to link the individual initiative OCB factor to normative commitment.

Hypothesis 5: Individual initiative has a positive influence on normative commitment.

The relationship between civic virtue and OC

The sixth main category of organizational citizenship behavior is civic virtue. According to Chen and Francesco (2003), civic virtue is characterized by behaviors that reflect an individual's deep concern and strong interest in the wellbeing and life of the organization (Podsakoff et al., 2000; Organ et al., 2006). An employee's sense of belonging to an organization and positive involvement in the concerns of the organization would be characteristics of civic virtue, in the same way citizens carry out their civic duty as a part of their country. Civic virtue is divided into two sub-categories: civic virtue-information, which includes participating in meetings that are not mandatory but are considered important, attending events that are not required but help in promoting the organization's image, reading documents containing the organization information, and remaining on the lookout for incoming news; and civic virtue-influence, which consists of an individual to be proactive and making suggestions for change (Graham and Van Dyne, 2006). The definition of civic virtue is in some manner similar to the definition of continuance commitment where the employee feels an obligation to express commitment to the organization by exercising civic virtue. The lack of such OCB could be considered a disloyal act which in turn would result in fatally impacting the employee's career path within the organization, and it may also negate the previous efforts put in by the employee to stay committed to the goals of the organization.

Hypothesis 6: Civic virtue has a positive influence on continuance commitment.

The relationship between self-development and OC

Podsakoff et al. (2000) and Organ et al. (2006) state the seventh main category of organizational citizenship behavior is self-development which "encompasses the discretionary measures people take to broaden their work-relevant skills and knowledge, including voluntary enrolment in company-sponsored training courses as well as the informal study" (Cetin, 2006). Self-development has a direct impact on organizational commitment. Roepke et al. (2000) reported that competency development practices such as job rotation programs, mentoring, and training convey to employees that the organization is seeking to establish a long-term relationship with them, hence, employees would be devoted to the organization because they would feel strongly invested in the organizational structure, which is an indicator for continuance commitment. Organ et al. (2006) have admitted that no research empirically supports self-development as a dimension of organizational citizenship behavior as the last category recognized for OCB.

Hypothesis 7: Self-development has positive influence on continuance commitment.

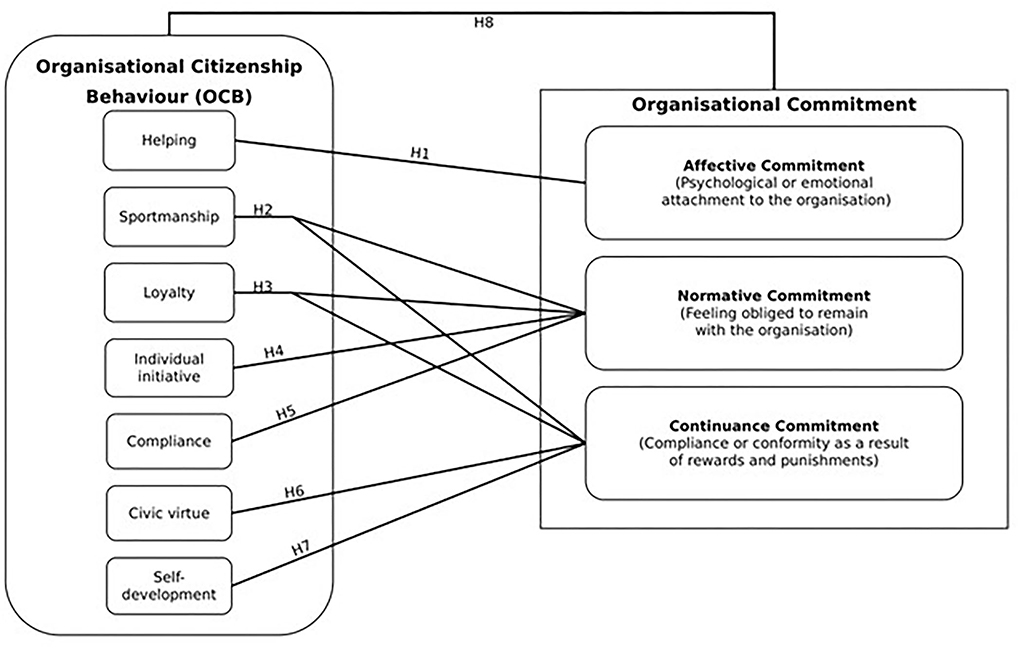

Proposed framework

Although reference to the term "organizational commitment" points to three very different concepts in Meyer and Allen's three-component model, an individual's psychological attachment to the organization remains a shared denominator of all three types of commitment, and it is, therefore, this psychological attachment factor that defines organizational commitment. In contrast to the expansive literature on OCB in non-educational study cases, Dipaola and Tschannen-Moran (2001) have confirmed a minimal number of documented literature on causal relationships between organizational commitment and OCB of faculty members and staff. Organ (1988) stated that context-specific organizational citizenship behaviors vary from one type of organization to another. Since the current literature does not provide a solid lead to definite hypotheses regarding the relationship between the factors of OCB of faculty members and staff and organizational commitment, it is the objective of this research to determine which factor best predicts the three types of commitment: affective commitment, normative commitment, and continuance commitment.

The acts of cooperating with colleagues, performing extra duties without complaining, being punctual, volunteering, helping peers, using time efficiently, preserving resources, sharing ideas, and positively representing the organization are practical consequences of organizational citizenship behavior (Turnipseed and Rassuli, 2005). They can be linked to the measurement scales for affective commitment, normative commitment, and continuance commitment. From previous hypotheses plotted for each factor of OCB, the relationship between organizational citizenship behavior of faculty members and staff and organizational commitment is to be stimulated by each factor of OCB that is positively influencing a type of commitment. Considering the seven factors of OCB as a whole, it is clear that OCB has a positive and direct influence on organizational commitment. Figure 1 exhibits the relationships, which was constructed based on suitable theories and above hypotheses.

Figure 1. The research framework.

Research methodology

Measures of the constructs

Both qualitative and quantitative methods were used to create the questionnaire for measuring the constructs. In the first stage, selected participants from higher education institutions contributed to the qualitative step. There were seven respondents, including senior lecturers, deans, human resources manager and vice presidents, who were interviewed for determining organizational commitment and organizational citizenship behavior in Vietnamese higher research institutions. The selected respondents were from the board of rectors, human resources managers as well as deans from International University, Vietnam National University Ho Chi Minh City (IU-VNU-HCM), Ho Chi Minh City University of Economics and Finance (UEF), and Ho Chi Minh City University of Technology (HUTECH). As a result of this stage, the questionnaire was modified and made suitable in the Vietnam context and ready for the quantitative research stage. The questionnaire for the quantitative stage included 89 questions, divided into two sections: demographic variables with seven questions and key observed variables with 81 questions that were derived from Meyer and Allen's (1997) three-component model (TCM) of commitment and the seven categories of OCB defined by Podsakoff et al. (2000) and Organ et al. (2006). The questionnaire aimed to measure a total of 10 factors, three of them dependent variables (affective commitment, normative commitment, and continuance commitment) and remaining seven independent variables (helping behavior, sportsmanship, organizational loyalty, individual initiative, organizational compliance, civic virtue, and self-development). The final questionnaire was created with closed questions and clear definitions with determinants of dimensions and how to measure the variables on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree).

Data collection and sampling technique

Based on the Ministry of Education and Training statistics, the ratio between public and private universities is ~3:1. Hence, researchers focused on achieving a similar 3:1 proportion of participants from public and private universities. The public universities that were selected are Ho Chi Minh City Open University (HCMCOU), Ho Chi Minh City Architecture University (UAH), Ho Chi Minh City University of Finance and Marketing (UFM), Sai Gon University (SGU), Ho Chi Minh City University of Transportation (UT-HCMC), Banking University of Ho Chi Minh City (BUH), Ho Chi Minh City University of Technology and Education (HCMUTE), and Vietnam National University Ho Chi Minh City and its affiliates such as the International University (IU), University of Social Sciences and Humanities (USSH), University of Science (US), University of Technology (UT), University of Information Technology (UIT), and University of Economics and Law (UEL). From the private sector, nine universities participated: Ho Chi Minh City Technology University (HUTECH), Ton Duc Thang University (TDTU), Van Lang University (VLU), Hong Bang University (HIU), Hoa Sen University (HSU), Ho Chi Minh University of Foreign Languages and Information Technology (HUFLIT), Ho Chi Minh City University of Economics and Finance (UEF), Gia Dinh University (GDU), and Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology campus in Ho Chi Minh City (RMIT). The data collection period was within the academic year 2020/2021, from January 2021 to May 2021, during the COVID-19 pandemic. Hence, the questionnaires were distributed online and faculty members and staff were instructed via email exchange to target the correct and appropriate population of respondents.

Data analysis and results

Methods of statistical analysis

This study used SmartPLS3.0 to optimize the variance explained by endogenous latent variables in the partial least square's structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) technique (Hair et al., 2011) and explain the proposed relationship. Kaplan (2008) suggested that "structural equation modeling (SEM) can best be defined as a class of methodologies that seeks to represent hypotheses about the means, variances, and co-variances of observed data in terms of a smaller number of 'structural' parameters defined by a hypothesized underlying model." In addition, this method is suitable when the sample size is small with a complex research model (Hair et al., 2019). The reliability analysis is compulsory, and the measurement scales were validated for accuracy in the reliability analysis step. The above processes are needed to acquire a realistic and precise study result. After the measurement models satisfy the criteria, the structural model evaluations can be undertaken. The PLS-SEM was used to investigate the models. Finally, the One-Way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) in SPSS was used to determine if any statistically significant differences occur between the distinct groups of the study.

Sample characteristics

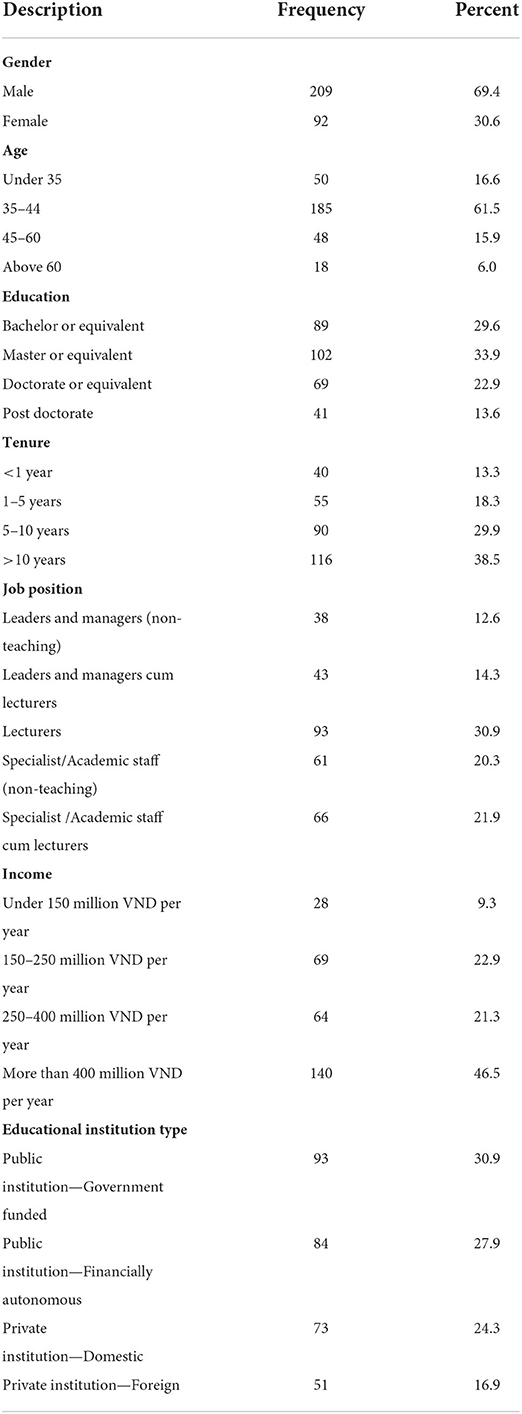

The survey questionnaire was sent to 30 Higher Education Institutions in Ho Chi Minh City. However, only 21 institutions approved the survey distribution to their faculty members and staff. A total of 450 questionnaires were distributed, and 353 questionnaires were returned with a return rate of over 78%. From these, 52 were excluded during the screening stage due to incomplete information. The demographic data showed that male respondents accounted for the majority of respondents with 69.4%, while female respondents were 30.6% of the total 301 valid responses. Among the respondents, 58.8% work in a public educational institution, and 24.3% work in a private domestic educational institution. The age of the respondents was diverse: 16.6% were under 35 years old, 61.5% of them between 35 and 45 years old, representing the most populated group of respondents with 185 people. About 6.0% of respondents were more than 60 years old. Most of the respondents (38.5%) of this research had over 10 years of experience in the education field. Only 40 respondents (13.3%) had less than 1 year of experience; 18.3% had between 1 and 5 years of experience. On level of education, 36.5% had a PhD or higher qualification; most of the respondents (33.9%) had a Master's or equivalent level of education.

In terms of job position, 30.9% of the respondents were full-time lecturers, 21.9% were specialists engaged in part-time teaching, 14.3% worked in a management position that required teaching, and 20.3% of the respondents were non-teaching specialists or employees. As information on incomes earned are confidential, the respondents were only asked to give information on their yearly salary range from their job in their respective institutions. About 140 respondents representing 46.5% of the study population earned more than 400 million VND per year. Sixty-four respondents (21.3%) made between 250 and 400 million VND annually. Sixty-nine respondents (22.9%) had a salary range between 150 and 250 million VND per year. The remaining 28 respondents (9.3%) made less 150 million VND per year (as per current estimate, one million Vietnamese Dong equals ~43 US dollars). A description of the respondents' characteristics is presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Description of the respondents' characteristics.

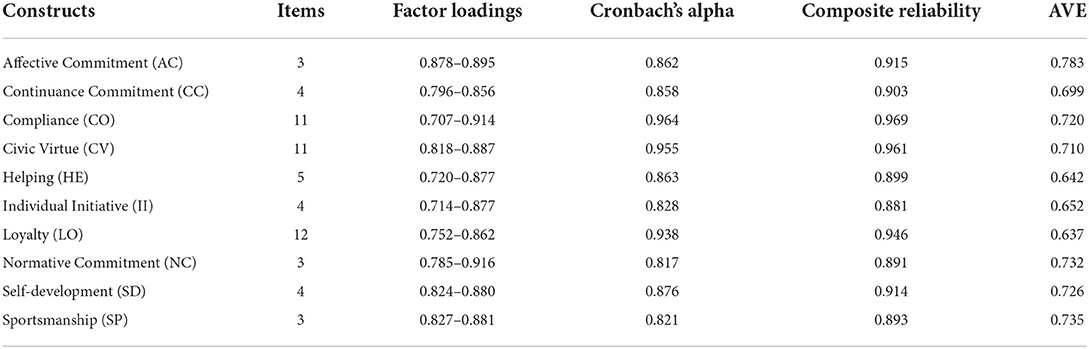

Evaluation of measurement model

Firstly, the study examined the outer loadings of indicators to check whether the constructs meet the requirements. As suggested, the loadings must be at least 0.7 (Hair et al., 2019). The results indicated that all outer loadings are more significant than the substantial value of 0.7 (in the range of 0.707–0.916). Next, internal consistency was evaluated by using Cronbach's α. The findings revealed that the inner loadings of all the variables are more significant than the threshold of 0.7 (Leguina, 2015). As seen in Table 2, the values of Cronbach's α ranged from 0.817 to 0.964, and the values of composite reliability ranged from 0.881 to 0.969, therefore confirming the high reliability of the data. Moreover, AVE values for all factors that were examined are greater than the minimum requirement (0.5), ranging from 0.637 to 0.783. Therefore, convergent validity was well-explained by the measurement model.

Table 2. Factor loadings and composite reliability of the measurement model.

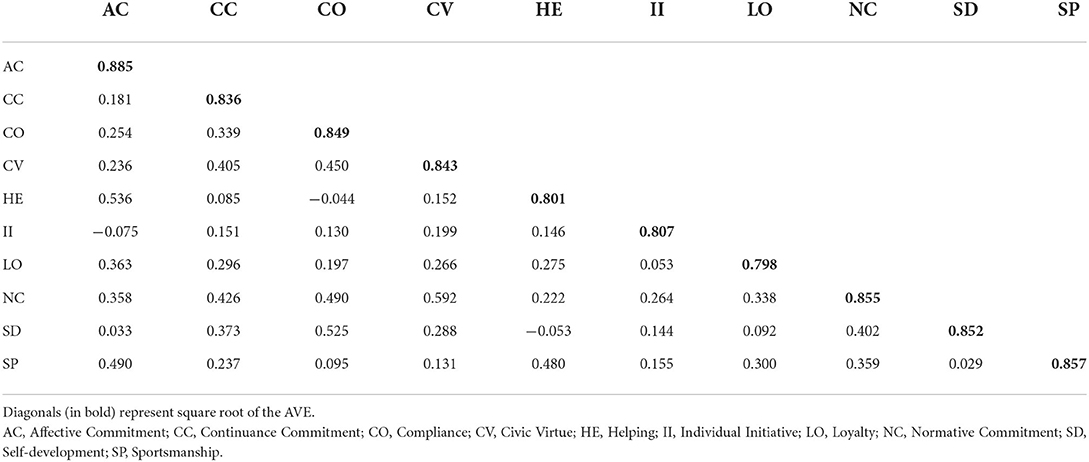

Additionally, discriminant validity is a vital criterion to be measured to understand the degree of variance of each variable in the model. Fornell and Larcker (1981) criterion is applied to validate the AVE of every latent construct, which should be greater than the most significant squared correlations between any other constructs. Table 3 indicates that the square root of the AVEs for each construct is larger than the cross-correlation with other constructs. Therefore, discriminant validity is acceptable in the measurement model.

Table 3. Result of the discriminant validity.

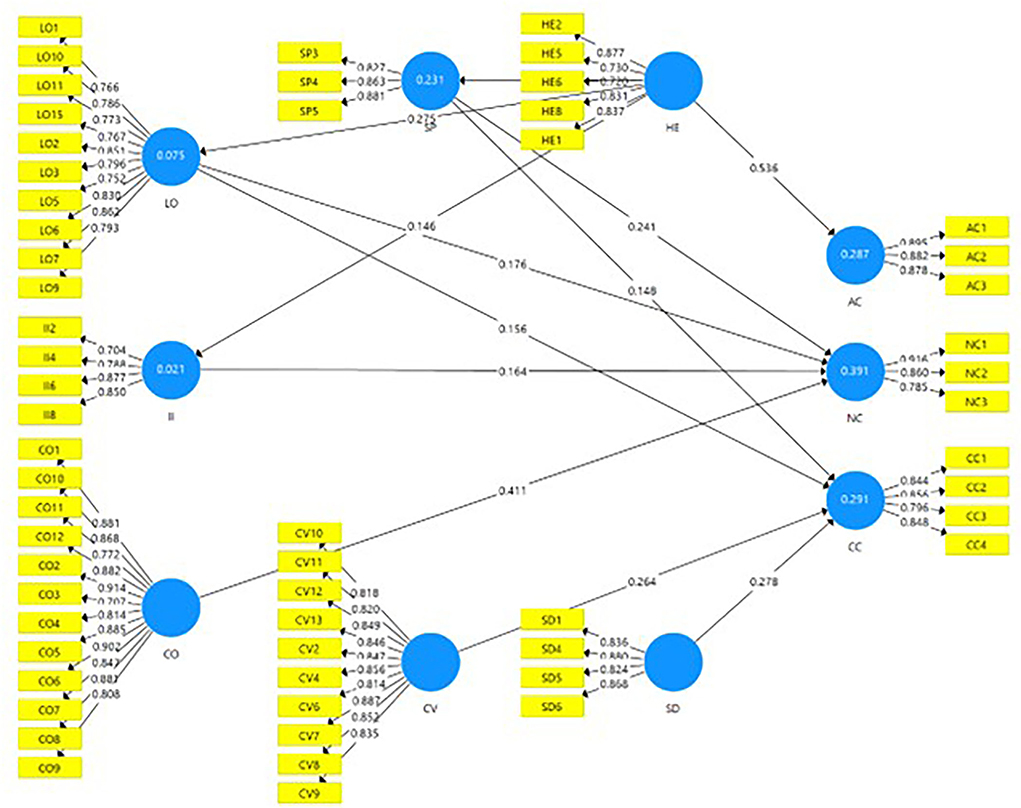

Evaluation of structural model and research findings

In the measurement model, all variables have qualified, so the structural model is suitable to test the assumptions. Hair et al. (2019) suggests several statistical tools such as coefficient of determination, collinearity assessment, effect size, and direct effect. Before testing the relationships between constructs, collinearity should be evaluated by variance inflation factor (VIF) and collinearity happens when the VIF value are >5.00. The results indicated that all the VIF values were <2, indicating no collinearity. R-square is used to estimate the predictive precision. Additionally, F-square is used to evaluate the influence of independent constructs on dependent constructs (Leguina, 2015). The R-square values range from 0 to 1. As a result, the R-square values were close to substantial for affective commitment (R-square = 0.285), continuance commitment (R-square = 0.282), and normative commitment (R-square = 0.383). The findings illustrate that independent variables of organizational citizenship behavior accounted for 28.5% of the variance in affective commitment, 28.2% in continuance commitment, and 38.3% in all variances in normative commitment. On the other hand, the three components of organizational commitment together demonstrated about 95% of variance in organizational citizenship behavior. The results of the R-square indicate that the structural model passed the level of predictive accuracy. F-square values show 0.02, 0.15, and 0.35 indicating the small, moderate, and large impact of independent variables on dependent ones, respectively (Leguina, 2015). The results moderate the effect of all constructs ranging from 0.022 to 0.403. Only helping behavior had a large effect on the affective commitment where the F-square is 0.403; others show lower effect with lower F-square values.

Finally, the coefficient significance is examined by PLS-SEM with a nonparametric bootstrapping method (Hair et al., 2014). In this research, the sample size had 301 cases with 1,000 subsamples. T-values were estimated to inspect the statistical significance of the coefficient.

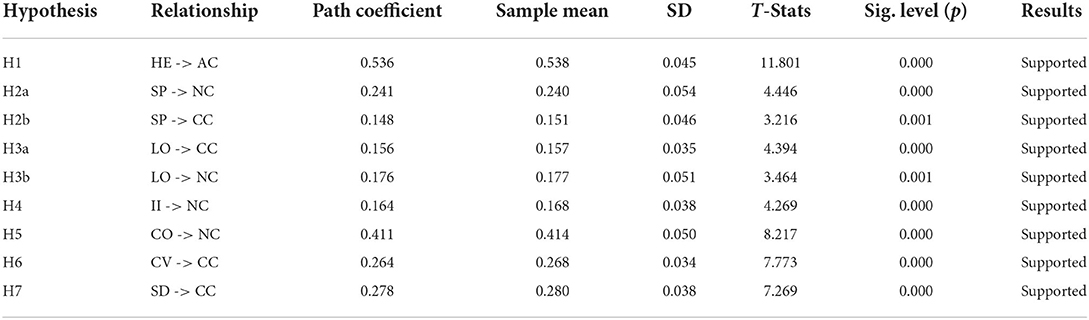

Table 4 presents the SEM results of the hypotheses testing and the path coefficients of the research's model in Figure 2. Seven proposed hypotheses were supported. The results confirmed hypothesis 1 (H1), which proposed helping behavior (HE) had a positive relationship with the increase in the affective commitment (AC) of higher educational institution employees. It implies that when employees receives support from the organization and colleagues, they feel like they belong to the organization. This finding coincides with Charbonneau and Wood (2018) and Grego-Planer (2019). Next, hypothesis 2 (H2a and H2b), which stated sportsmanship (SP) has a positive relation with normative commitment (NC) and continuance commitment (CC), was accepted. It implies that when an organization brings the belief of fairness in its treatment, employees will be highly attached to their organization and get involved in its affairs. This finding supports the study results of Ghazanfar and Anjum (2018), Kim et al. (2020), Fauzi (2021), and Roncesvalles et al. (2021).

Table 4. Model's path co-efficient.

Figure 2. Structural equation modeling (SEM) diagram.

Hypothesis 3 (H3a and H3b) was also supported. It indicated that the increase in loyal behaviors (LO), such as protecting and defending the organization against possible external threats and promoting it to outsiders will lead to normative and continuance commitment. This result is associated with the findings of Han et al. (2018), Yao et al. (2019), and Krajcsák (2019). Further, this study's results confirmed hypothesis 4 (H4) and hypothesis 5 (H5), which determined the positive association of individual initiative (II) and compliance (CO) to normative commitment (NC). Hypothesis 6 (H6) and hypothesis 7 (H7), which proposed the positive relation of civic virtue (CC) and self-development (SD) to continuance commitment (CC) were accepted. These results support the findings of Shao (2018) and Ficapal-Cusí et al. (2020), which agreed that continuance commitment is affected by behaviors of civic virtue and the self-development of employees. Overall, the results reflect that the components of organizational citizenship behavior have positive impact on organizational commitment.

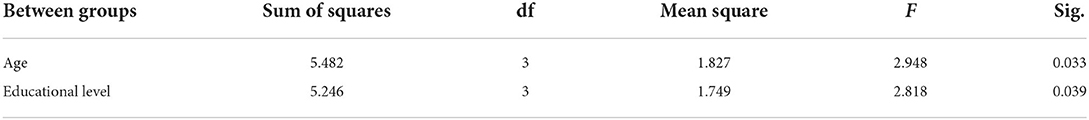

To determine if any statistically significant differences occur between the distinct groups of the study, the One-Way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) is employed. Seven variables (gender, age, seniority, educational level, job position, income, and institution type) were tested, but only age (0.033) and educational level (0.039) indicated a difference in the organizational commitment between groups (Table 5).

Table 5. ANOVA, F-test for age, and educational level variables.

Discussion and conclusion

This study has meaningful contributions to the literature. The first contribution is establishing a comprehensive relationship between organizational citizenship behavior and organizational commitment, particularly in higher educational institutions in Vietnam. The results indicated that OCB's components strongly affect organizational components in their own ways. The helping factor directly impacts affective commitment but also has indirect effect on normative and continuance commitment through its impact on loyalty and individual initiative factors. Secondly, this study reveals the relation between sportsmanship, organizational loyalty, individual initiative, organizational compliance, and normative commitment. Through that, it shows the ways for higher education institutions managers to increase the commitment of their employees. Thirdly, sportsmanship, organizational loyalty, civic virtue, and self-development affect positively the continuance commitment. Based on this, senior management at universities could choose a suitable strategy for improving the performance of their faculty and staff. Even though all organizational citizenship behavior components positively affected organizational commitment, the strongest influence was the helping factor followed by the organizational compliance factor, whereas the effects of others were similar.

From the observations made from analyzing the data set, it is preferable to recruit faculty members and staff that have an appropriate level of education for the job position offered, especially when it requires teaching. It is a strict requirement as established by the educational system and also a fundamental part of an educational institution to grow in strength and reputation. The reasoning behind this recommendation is that respondents with higher educational levels have shown that they are more committed to doing their job and participating in the development of the institution. They are voluntarily going the extra mile to reach their organization's goal. Lastly, the most important contribution is that the study draws a complete scenario of relations between organizational commitment and organizational citizenship behavior, especially in the field of higher educational institutions, which has received inadequate attention thus far. The results of the study corroborate with those of Srivastava (2008), Asiedu et al. (2014), Lambert et al. (2020), and Nugroho et al. (2020), which indicate that organizational citizenship behavior has a strong positive impact on organizational commitment.

Although this study focuses on higher educational institutions, the respondents are only from universities, representing an exclusive and limited sample. In addition, the study focuses on a narrow geographical area—Ho Chi Minh City; hence the findings might not be sufficiently indicative nor conclusive to generalize to all faculty members and staff in Vietnam. Future research should broaden the scope of sample size to also include vocational colleges. In addition, due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the sample size in this research was 301. It is not large enough to represent the entire population and reflects the 3:1 ratio of public and private universities in Vietnam. Therefore, further study should validate the findings of this study with a larger sample size with a reasonable ratio. Moreover, only Vietnamese higher educational institutions are focused on in this study; it is not enough to represent other educational systems in the rest of Asia. Thus, researchers could reexamine these findings in other contexts in future studies. Based on these results, senior management in higher educational institutions should study the effect of organizational citizenship behavior on organizational commitment of lecturers and staff in their universities. Policymakers should develop and implement human resources practices to increase organizational citizenship behavior and employee commitment in higher educational institutions, and the consequent improvement in quality will be reflected in a capacitated and qualified workforce (Harvey et al., 2018).

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

PN conceived the research topic, outlined the research design, supervised the whole process of the preparation of the article, read and commented on the manuscript several times, and submitted the manuscript to the journal. DL collected the data, wrote the initial drafts of the article, and revised the article based on PN's comments. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This work was supported by the Vietnam National University Ho Chi Minh City (VNU-HCM) under Grant Number C2020-28-05.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Allen, N. J., and Meyer, J. P. (1990). The measurement and antecedents of affective, continuance and normative commitment to the organization. J. Occup. Psychol. 63, 1–18. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8325.1990.tb00506.x

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Asiedu, M., Sarfo, J. O., and Adjei, D. (2014). Organisational commitment and citizenship behaviour: tools to improve employee performance; an internal marketing approach. Euro. Scient. J. 10. doi: 10.13140/2.1.3661.7923

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Bateman, T. S., and Organ, D. W. (1983). Job satisfaction and the good soldier: the relationship between affect and employee "citizenship". Acad. Manag. J. 26, 587–595. doi: 10.5465/255908

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Beck, K., and Wilson, C. (2000). Development of affective organizational commitment: a cross-sequential examination of change with tenure. J. Voc. Behav. 56, 114–136. doi: 10.1006/jvbe.1999.1712

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Becker, G. S. (2009). Human Capital: A Theoretical and Empirical Analysis, With Special Reference to Education. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Google Scholar

Bidarian, S., and Jafari, P. (2012). The relationship between organizational justice and organizational trust. Proc. Soc. Behav. Sci. 47, 1622–1626. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.06.873

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Cetin, M. O. (2006). The relationship between job satisfaction, occupational and organizational commitment of academics. J. Am. Acad. Bus. 8, 78–88.

Google Scholar

Charbonneau, D., and Wood, V. M. (2018). Antecedents and outcomes of unit cohesion and affective commitment to the army. Military Psychol. 30, 43–53. doi: 10.1080/08995605.2017.1420974

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Chen, Z. X., and Francesco, A. M. (2003). The relationship between the three components of commitment and employee performance in China. J. Voc. Behav. 62, 490–510. doi: 10.1016/S0001-8791(02)00064-7

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Deepaen, W., Pashiphol, S., and Sujiva, S. (2015). Development and preliminary psychometric properties of teachers' organizational citizenship behavior scale. Proc. Soc. Behav. Sci. 191, 723–728. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.04.710

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Devece, C., Palacios-Marqués, D., and Alguacil, M. P. (2016). Organizational commitment and its effects on organizational citizenship behavior in a high-unemployment environment. J. Bus. Res. 69, 1857–1861. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2015.10.069

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Dipaola, M., and Tschannen-Moran, M. (2001). Organizational citizenship behavior in schools and its relationship to school climate. J. School Leaders. 11, 424–447. doi: 10.1177/105268460101100503

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Eisenberger, R., Fasolo, P., and Davis-Lamastro, V. (1990). Perceived organizational support and employee diligence, commitment, and innovation. J. Appl. Psychol. 75, 51. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.75.1.51

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Esnard, C., and Jouffre, S. (2008). Organizational citizenship behavior: social valorization among pupils and the effect on teachers' judgments. Eur. J. Psychol. Educ. 23, 255–274. doi: 10.1007/BF03172999

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Fauzi, H. (2021). Effect of job satisfaction and organizational commitment on organizational citizenship behavior at PDAM Head Office Majalengka Regency. Enrichment 12, 212–218.

Google Scholar

Ficapal-Cusí, P., Enache-Zegheru, M., and Torrent-Sellens, J. (2020). Linking perceived organizational support, affective commitment, and knowledge sharing with prosocial organizational behavior of altruism and civic virtue. Sustainability 12, 10289. doi: 10.3390/su122410289

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Fornell, C., and Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Market. Res. 18, 39–50. doi: 10.1177/002224378101800104

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Gautam, T., Van Dick, R., Wagner, U., Upadhyay, N., and Davis, A. J. (2005). Organizational citizenship behavior and organizational commitment in Nepal. Asian J. Soc. Psychol. 8, 305–314. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-839X.2005.00172.x

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Ghazanfar, A., and Anjum, S. (2018). The moderating role of gender in the relationship among organizational justice, commitment, job satisfaction and organizational citizenship behaviors of secondary school teachers. Pak. J. Educ. 35, 566. doi: 10.30971/pje.v35i1.566

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Graham, J. W., and Van Dyne, L. (2006). Gathering information and exercising influence: two forms of civic virtue organizational citizenship behavior. Employee Responsibil. Rights J. 18, 89–109. doi: 10.1007/s10672-006-9007-x

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Greenberg, J., and Cropanzano, R. (1993). The Social Side of Fairness: Interpersonal and Informational Classes of Organizational Justice. Justice in the Workplace: Approaching Fairness in Human Resource Management. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Google Scholar

Grego-Planer, D. (2019). The relationship between organizational commitment and organizational citizenship behaviors in the public and private sectors. Sustainability 11, 6395. doi: 10.3390/su11226395

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Griffin R. W. and Bateman, T. S.. (1986). "Job satisfaction and organizational commitment," in International Review of Industrial and Organizational Psychology, eds C. L. Cooper and I. T. Robertson (Chichester: Wiley), 157–188.

Google Scholar

Hair Jr, J. F., Sarstedt, M., Hopkins, L., and Kuppelwieser, V. G. (2014). Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM): An emerging tool in business research. Euro. Bus. Rev. 26, 106–121. doi: 10.1108/EBR-10-2013-0128

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Hair, J. F., Page, M., and Brunsveld, N. (2019). Essentials of Business Research Methods. London: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9780429203374

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Hair, J. F., Ringle, C. M., and Sarstedt, M. (2011). PLS-SEM: Indeed a silver bullet. J. Market. Theor. Pract. 19, 139–152. doilink[10.2753/MTP1069-6679190202]10.2753/MTP1069-6679190202

Google Scholar

Han, H., Kiatkawsin, K., and Kim, W. (2018). Traveler loyalty and its antecedents in the hotel industry: impact of continuance commitment. Int. J. Contempor. Hospital. Manag. 2017, 237. doi: 10.1108/IJCHM-04-2017-0237

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Harvey, J., Bolino Mark, C., and Kelemen Thomas, K. (2018). "Organizational citizenship behavior in the 21st century: how might going the extra mile look different at the start of the new millennium? in Research in Personnel and Human Resources Management, eds M. R. Buckley, R. W. Anthony, and R. B. H. Jonathon (Bingley: Emerald Publishing Limited). doi: 10.1108/S0742-730120180000036002

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Kaplan, D. (2008). Structural Equation Modeling: Foundations and Extensions. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

PubMed Abstract | Google Scholar

Kim, S.-H., Kim, M., and Holland, S. (2020). Effects of intrinsic motivation on organizational citizenship behaviors of hospitality employees: the mediating roles of reciprocity and organizational commitment. J. Hum. Resour. Hospital. Tour. 19, 168–195. doi: 10.1080/15332845.2020.1702866

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Kim, W. G., Leong, J. K., and Lee, Y.-K. (2005). Effect of service orientation on job satisfaction, organizational commitment, and intention of leaving in a casual dining chain restaurant. Int. J. Hospital. Manag. 24, 171–193. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2004.05.004

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Krajcsák, Z. (2019). Implementing open innovation using quality management systems: the role of organizational commitment and customer loyalty. J. Open Innov. 5, 90. doi: 10.3390/joitmc5040090

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Lambert, E. G., Keena, L. D., Leone, M., May, D., and Haynes, S. H. (2020). The effects of distributive and procedural justice on job satisfaction and organizational commitment ofcorrectional staff. Soc. Sci. J. 57, 405–416. doi: 10.1016/j.soscij.2019.02.002

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Leguina, A. (2015). A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). Int. J. Res. Method Educ. 38, 220–221. doi: 10.1080/1743727X.2015.1005806

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Markovits, Y., Davis, A. J., Fay, D., and Dick, R. V. (2010). The link between job satisfaction and organizational commitment: differences between public and private sector employees. Int. Publ. Manag. J. 13, 177–196. doi: 10.1080/10967491003756682

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Mercurio, Z. A. (2015). Affective commitment as a core essence of organizational commitment: an integrative literature review. Hum. Resour. Dev. Rev. 14, 389–414. doi: 10.1177/1534484315603612

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Meyer, J. P., and Allen, N. J. (1997). Commitment in the Workplace: Theory, Research, and Application. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. doi: 10.4135/9781452231556

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Meyer, J. P., Allen, N. J., and Smith, C. A. (1993). Commitment to organizations and occupations: extension and test of a three-component conceptualization. J. Appl. Psychol. 78, 538. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.78.4.538

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Moorman, R. H. (1991). Relationship between organizational justice and organizational citizenship behaviors: do fairness perceptions influence employee citizenship? J. Appl. Psychol. 76, 845. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.76.6.845

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Moorman, R. H., Niehoff, B. P., and Organ, D. W. (1993). Treating employees fairly and organizational citizenship behavior: sorting the effects of job satisfaction, organizational commitment, and procedural justice. Employee Responsibil. Rights J. 6, 209–225. doi: 10.1007/BF01419445

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Nugroho, B. S., El Widdah, M., and Hakim, L. (2020). Effect of organizational citizenship behavior, work satisfaction and organizational commitment toward Indonesian School Performance. Systemat. Rev. Pharm. 11, 962–971. doi: 10.31838/srp.2020.9.140

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Organ, D. W. (1988). Organizational Citizenship Behavior: The Good Soldier Syndrome. Lexington: Books/DC Heath and Com.

Google Scholar

Organ, D. W., Podsakoff, P. M., and Mackenzie, S. B. (2006). Organizational Citizenship Behavior: Its Nature, Antecedents, and Consequences. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. doi: 10.4135/9781452231082

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Podsakoff, P. M., Mac kenzie, S. B., and Podsakoff, N. P. (2016). Recommendations for creating better concept definitions in the organizational, behavioral, and social sciences. Org. Res. Methods 19, 159–203. doi: 10.1177/1094428115624965

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Paine, J. B., and Bachrach, D. G. (2000). Organizational citizenship behaviors: A critical review of the theoretical and empirical literature and suggestions for future research. J. Manag. 26, 513–563. doi: 10.1177/014920630002600307

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Porter, L. W., Steers, R. M., Mowday, R. T., and Boulian, P. V. (1974). Organizational commitment, job satisfaction, and turnover among psychiatric technicians. J. Appl. Psychol. 59, 603. doi: 10.1037/h0037335

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Robbins, S. P., and Judge, T. (2012). Essentials of Organizational Behavior, 11th Edn. Pearson.

Google Scholar

Roepke, R., Agarwal, R., and Ferratt, T. W. (2000). Aligning the IT human resource with business vision: the leadership initiative at 3M. Mis Quarterly 327–353. doi: 10.2307/3250941

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Roncesvalles, M., Celia, T., and Gaerlan, A. A. (2021). The role of authentic leadership and teachers' organizational commitment on organizational citizenship behavior in higher education. Int. J. Educ. Leaders. Manag. 9, 92–121. doi: 10.21474/IJAR01/10296

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Shao, Z. (2018). Examining the impact mechanism of social psychological motivations on individuals' continuance intention of MOOCs: the moderating effect of gender. Internet Res. 2016, 335. doi: 10.1108/IntR-11-2016-0335

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Srivastava, S. (2008). Organizational citizenship behaviour as a function of organizational commitment and corporate citizenship in organizations. Manag. Labour Stud. 33, 311–337. doi: 10.1177/0258042X0803300301

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Turnipseed, D. L., and Rassuli, A. (2005). Performance perceptions of organizational citizenship behaviours at work: a bi-level study among managers and employees. Br. J. Manag. 16, 231–244. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8551.2005.00456.x

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Wasti, S. A., and Can, Ö. (2008). Affective and normative commitment to organization, supervisor, and coworkers: do collectivist values matter? J. Voc. Behav. 73, 404–413. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2008.08.003

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Yao, T., Qiu, Q., and Wei, Y. (2019). Retaining hotel employees as internal customers: effect of organizational commitment on attitudinal and behavioral loyalty of employees. Int. J. Hospital. Manag. 76, 1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2018.03.018

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

tennysonthaboated.blogspot.com

Source: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2022.909263/full

0 Response to "Higher Organizational Continuance Commitment Leads to Higher Employeeas Citizenship Behaviors"

Post a Comment